Expanded from my original piece, published on the Blaze.

The Trump Administration has extended the global trade negotiation deadline to August 1, 2025:

So far, less than a handful of countries have been able to work out interim deals, including the United Kingdom, Vietnam, and (ironically) China.

A few others, like India, have offered zero-for-zero tariffs with the United States—free trade, at least on paper.

President Trump’s team has so far avoided making any “free trade” deals. They are right to be skeptical. Why?

Real global free trade—much like real communism—has never been tried! And this is not for lack of trying. It’s because it is impossible.

In reality, different countries are different; they have different levels of economic development, different laws, and different business cultures. These differences add up to make international free trade practically impossible.

Rather than hunting unicorns on behalf of doe-eyed economists, President Trump should pursue deals that put America first. After all, if the board is tilted, we may as well tilt it in our favor.

hunting unicorns

Different countries are different. And not just different in nominal ways—different in real, tangible ways that prevent seamless economic integration.

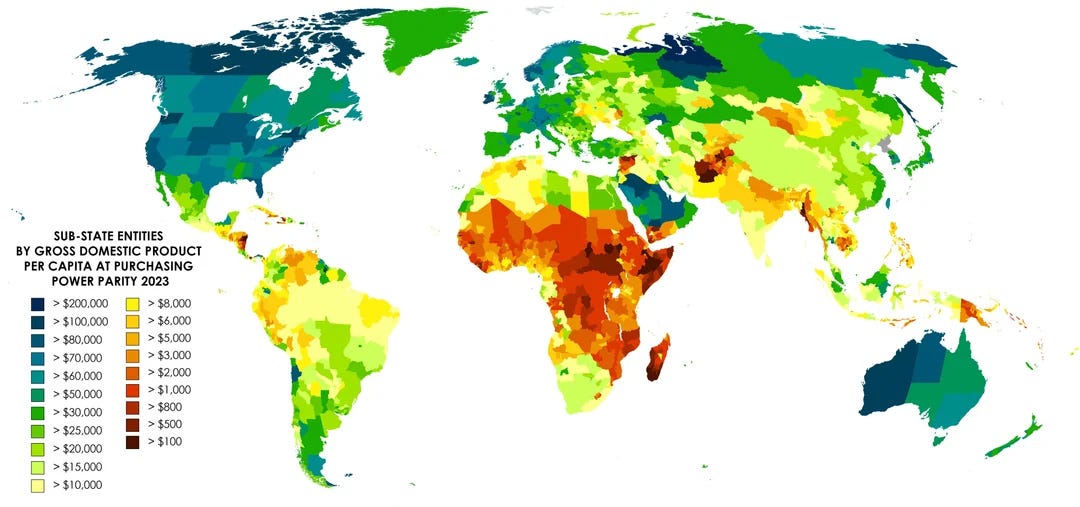

The most obvious example of this are differences in the price of labor. In 2024, the median annual income in America is about $44,000. Meanwhile, the median annual income in India is just $2,400. This means that the median American earns over 18 times as much as the median Indian.

This is a huge difference, especially since the cost of labor is often the largest input cost for making products. In fact, labor costs account for approximately 30-35% of the cost of American manufacturing. Labor costs are even higher in most service industries. This gives India a tremendous cost advantage over America—similar to the cost advantage that was enjoyed by China in 2001, when China joined the World Trade Organization.

Consider what would happen if the United States and India truly embraced free trade. It seems likely that American companies would offshore as much protection as possible to India to take advantage of cheap Indian labor. Why pay Americans $44,000 when they can pay Indians $2,400?

In fact, I can guarantee this will happen. Why? Because the exact same thing happened with China 25 years ago.

Deja vu.

In 2001 the average annual wage in America was $30,846 while the average annual wage in China was just $1,127—the average American earned 27x more than the average Chinese. What happened when American workers competed with Chinese workers? American factories moved to China and our wages stagnated.

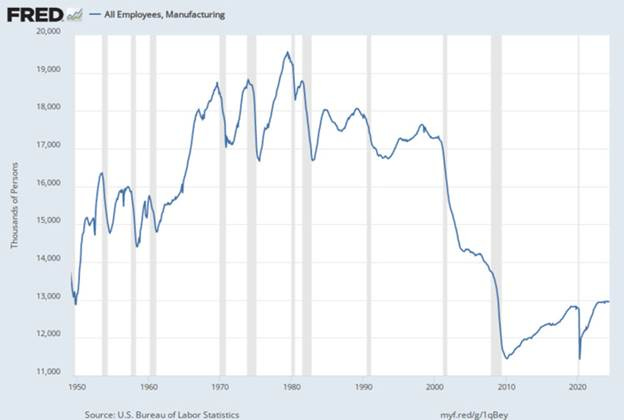

The pace of offshoring was harrowing. Since 2001 over 60,000 factories moved abroad, killing over 5 million manufacturing jobs. This has decimated America’s industrial capacity and hollowed-out local communities. And no, robots and automation are not to blame, in case you were curious.

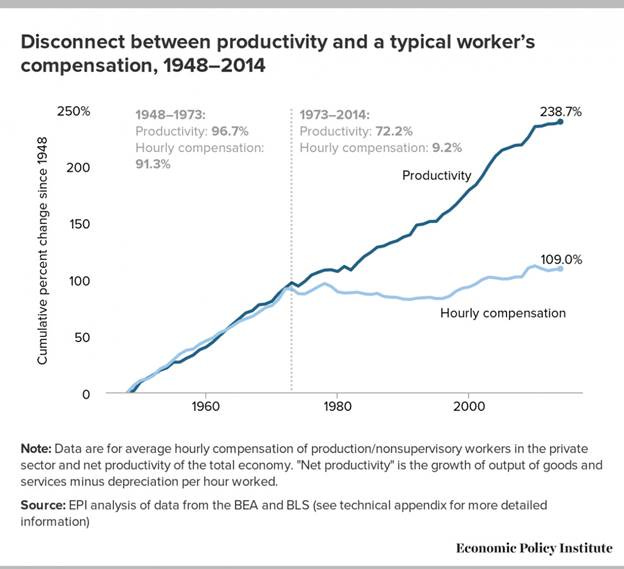

In fact, the process has been going on even earlier than 2001. America has run global trade deficits every year since 1974. The cumulative value of these deficits is $25 trillion, after adjusting for inflation. This has decoupled wages for American workers from their productivity—even though workers produce more value, they aren’t paid for it. Why? Because the wages are suppressed by competition with cheap foreign labor.

Of course, this logic does not just apply to India—it applies everywhere. Remember, American wages are amongst the highest in the world. This means that most developing countries pose a potential threat to American industry.

Why tariffs—like diamonds—are forever

It’s pretty obvious how big differences in labor prices can lead to offshoring. It’s basic math. But what about when two countries have similar levels of economic development? Is free trade possible?

Not necessarily. Remember, a product’s cost is not always the same as its price. Many costs that may be baked into the price of an American product are not baked into the cost of foreign products—and vice versa.

For example, relative to the developing world, the United States has strict regulations that help balance economic interests with other important societal goals, such as ensuring reasonable workplace standards or protecting the environment. These standards impose costs on producers—it costs money to give workers lunchbreaks or to remediate toxic waste—and these costs are baked into the final price of an American-made product. The costs are internalized.

On the other hand, countries like China, India, or Mexico do not have robust regulations. As a result, their goods are “cheaper” than American goods—at least on paper.

But in reality, the costs are still incurred. They are simply externalized from the producer of a product to society at large. For example, there are moral costs associated with using slave labor to manufacture spatulas. There is an environmental cost associated with dumping poisonous sludge or microplastics into the ocean. There is a health cost associated with eating parasite-ridden food grown in unsanitary foreign countries.

Although these costs directly harm the American people, they are not reflected in the sticker price of foreign products. This gives imported products the illusion of being “cheap”, when in reality they are often just cheaply made.

What profits a man…

Rather than asking whether free trade is possible, we should ask whether free trade is desirable. Is it in America’s best interests to offshore our manufacturing capacity to China, India, or Mexico? Or are there non-economic reasons that we should be self-sufficient?

The Founding Fathers certainly thought so. Recall that the Tariff Act of 1789 was explicitly passed in order to help America develop its own industrial base.

We would be wise to remember that money isn’t everything. America is not an economy. America is a nation bound together by blood and tradition, language and culture, through faith in freedom and with trust in God.

In that vein, economic self-sufficiency has an existential value all of its own.

The “illusion of cheap” point is one of the sharpest lines in the piece. It gets to the core of why this isn’t just about economics. It’s about values embedded in price tags.

What stood out to me is how often we confuse trade liberalism with moral neutrality. But systems aren’t neutral if they reward the externalization of harm. That’s not free trade. It’s subsidized abuse by another name.

If tariffs are the tool to rebalance incentives, how do we make sure they support national resilience without calcifying inefficiency or entrenching bad actors at home? Because protectionism alone won’t rebuild a healthy industrial base; it just buys us time to do the hard work. Are we using that time well?