Robots Didn't Take Our Jobs—China Did

Trade—not automation—is not to blame for America's manufacturing decline

~Originally published in Blaze, content updated~

Dylan Matthews argues in Vox that even if President Trump’s tariffs reshore factories, they will not create jobs as promised. Why?

Matthews argues that America’s manufacturing job loss was not caused by offshoring to China. Instead, it is one of the “inevitable effects of rising productivity in the manufacturing sector.” Basically, robots—not the Chinese—took the jobs.

Matthews is wrong. Not only did “free” trade—or rather asymmetrical and unfair trade—with China kill the jobs, but tariffs are the best way to bring them back.

Tin Lizzie’s revenge

In 1908 Henry Ford—America’s greatest industrialist—released his latest and greatest automobile, the Model T. What made the Model T so special? Its sticker price: the Tin Lizzie cost just $850, or roughly $21,000 in today’s money.

This was a watershed moment in American history. For the first time ever, middle class citizens could afford a personal vehicle. Henry Ford spent the next few years exploring ways to cut costs, so that he could realize his dream of bringing automobiles to the masses.

In December 1913, Ford Motor Company opened the world’s first factory with a mobile assembly line. This factory was an order of magnitude more efficient than any of its predecessors. In fact, Ford was able to reduce the time it took to build the Model T from 12 hours to just 93 minutes.

Greater productivity led to greater production. In 1914 Ford produced 308,162 Model Ts—more automobiles than all other manufacturers combined. Prices also dropped. By 1924 a new Model T cost just $260, or roughly $3,500 today. This was fully 83 percent cheaper than what a Model T cost just a decade early—and much cheaper than mass market automobiles today.

The Automobile Age had begun.

Henry Ford’s mobile assembly line dramatically increased productivity and therefore reduced the need for human labor. And yet, Ford did not fire his workers—he hired more. How do we reconcile this apparent paradox?

The solution is deceptively simple—and lost on Dylan Matthews. Employment is a balancing act between productivity and output. Productivity refers to how much value a worker can produce per hour. Output refers to how much value is produced in total.

All else equal: if productivity increases, then fewer workers are needed to produce the same value. For example, a worker with a digger can move more dirt than someone with a shovel. Conversely, if output increases, then more workers are needed to produce this value—if you want to move double the dirt, then you need twice as many shovellers.

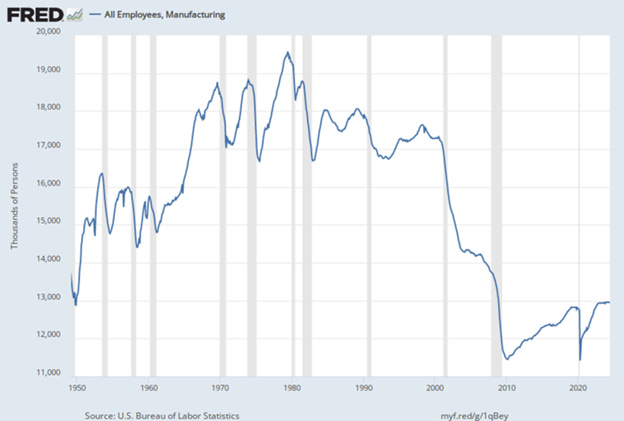

Accordingly, employment will only decrease if productivity increases faster than output. This was Henry Ford’s secret: although Ford dramatically increased worker productivity, he also built many more cars. This logic explains why America’s manufacturing employment peaked in 1979—half a century after newspapers claimed that Ford’s machines made humans obsolete.

The vanishing act

Matthews claims that manufacturing employment decreased because productivity increased. This is half true. The full story is that America lost manufacturing jobs because the historic balance between productivity and output shifted.

Between 1950 and 1979 manufacturing employment increased. Why? During this period, output increased faster than productivity. Over the next few decades the balance began to shift.

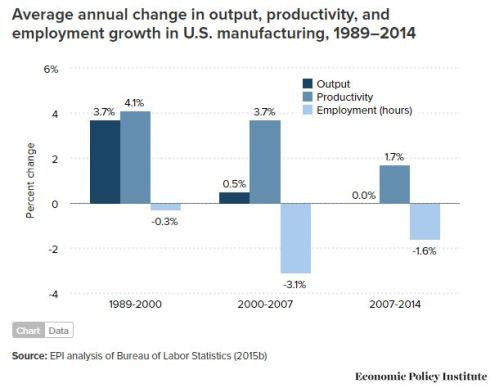

For example, between 1989 and 2000 American manufacturing output grew by 3.7% on average, while productivity grew by 4.1%. Employment remained relatively stagnant, as the two grew in tandem.

The rubber really hit the road after 2001, when China joined the World Trade Organization. Over the next 10 years America’s manufacturing output grew by just 0.4%. Meanwhile, productivity continued to increase by 3.7%. This imbalance between productivity and output growth killed roughly 5 million manufacturing jobs.

Matthews, or perhaps more accurately the economists he cites, claims that productivity increases caused America’s manufacturing job loss. But like I said, this is only half true. Productivity is just one half of the equation. What killed the jobs was that output stopped increasing at the same rate. Remember, manufacturing employment continued to increase from 1913 to 1979—despite massive productivity gains.

What caused America’s output growth to collapse? The trade deficit.

Feeding the dragon

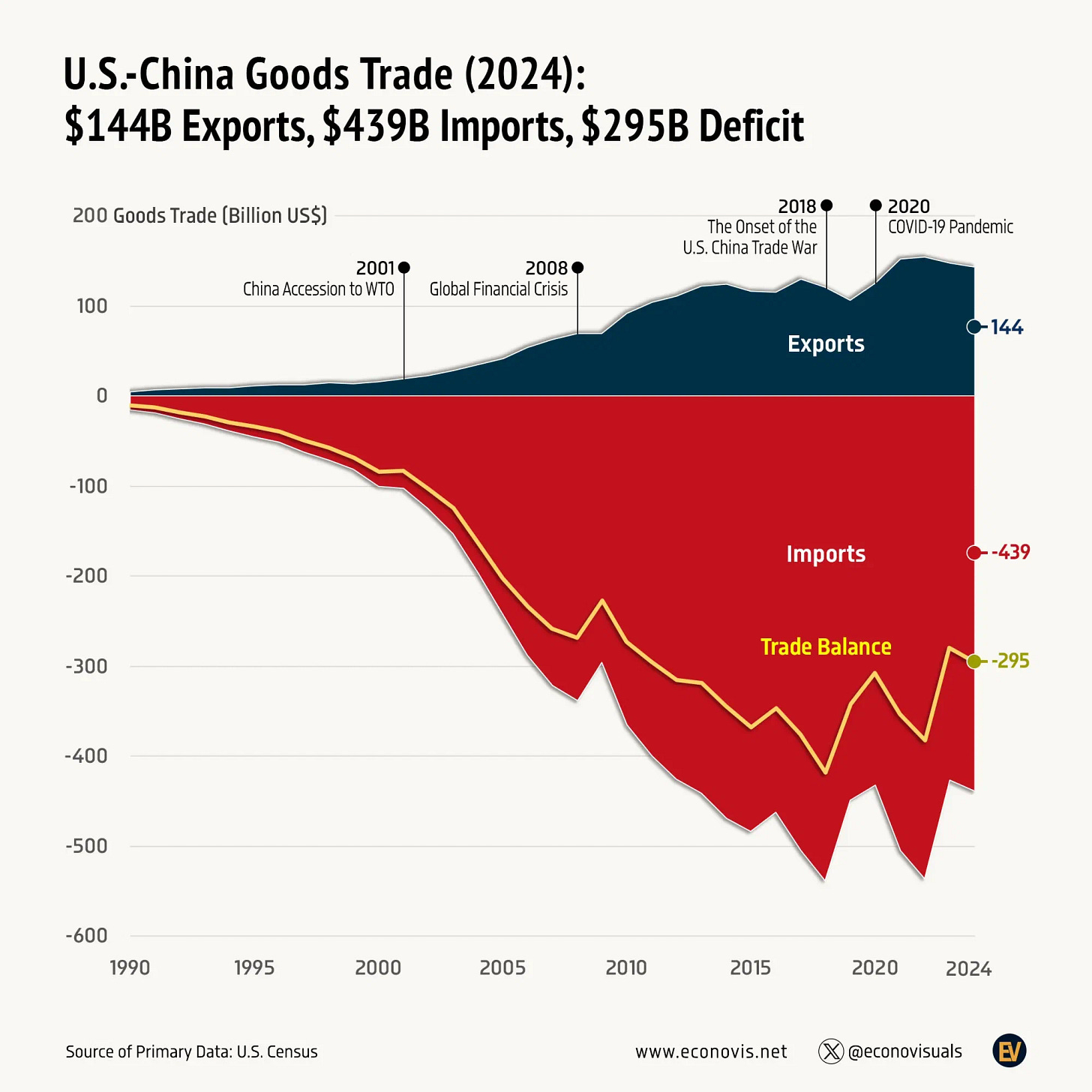

Since 1974—and particularly since 2001—America’s domestic output growth slowed dramatically, even though American workers continued to grow more productive. This is because thousands of factories were offshored to China and other developing countries because of market asymmetries and foreign industrial policies.

The value of America’s displaced economic production is reflected in the trade deficit.

In 2024, America’s net trade deficit was $918 billion—this includes the services surplus. This means that American consumed this much more than we produced. Of course, someone had to make these goods. In this case, mostly China, Mexico, Canada, and the European Union.

Accordingly, the trade deficit literally represents the value of America’s offshored economic production—rather than build it, we buy it.

How many jobs does the trade deficit displace? The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that every billion of GDP supports between 5,000 and 5,500 jobs. Based on this, we can estimate that the trade deficit displaces between 4.6 and 5 million jobs—mostly manufacturing jobs. Not so coincidentally, this is approximately the same amount of manufacturing jobs that have been lost since the 1990s.

On top of this, we need to remember that factories function like mines or farms: they are anchor industries upon which service industries depend. As such, they support other jobs that would not exist without them. Economists have studied this and call it the multiplier effect. Manufacturing has one of the highest multiplier effects of all industries, with each manufacturing job supporting between 1.8 and 2.9 predicate jobs (depending on the type of manufacturing).

This means that the number of jobs lost to offshoring are probably understated—the true damage could be well over 10 million jobs. This is, not-so-coincidentally, the approximate number of the people written who were written out of the labor force by the Bureau of Labor Statistics since 2006, as detailed in my book Reshore: How Tariffs Will Bring Our Jobs Home & Revive the American Dream.

At this point it should be clear that Dylan Matthews has it entirely wrong: robots are not to blame. In reality, America’s manufacturing productivity has improved at a relatively steady pace for over a century. During this time, manufacturing employment grew or remained steady.

It was not until the “free trade brigade” of globalists, neocons, and economic liberals worked in tandem to offshore thousands of factories to the developing world that America’s output growth flatlined. Incompetent and asymmetrical trade policies—not robots—is squarely to blame for America’s manufacturing decline.

The silver lining is that this process is not “inevitable”. Instead, the damage is entirely reversable through the sensible use of tariffs.